Koichi Hoshino,Munetaka Hibi

Japan Shiatsu CollegeShiatsu Department

Hiroyuki Ishizuka

Japan Shiatsu CollegeShiatsu instructor

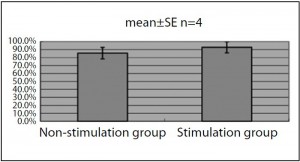

Abstract : There are few studies on the effects of plantar region shiatsu treatment on the locomotor system. In this study, we examined the effects of shiatsu stimulation of the plantar region on standing balance, based on measurements obtained using a stabilograph. Four healthy subjects received shiatsu treatment to the plantar region for 1 min 42 sec per session. Results showed no significant differences between the stimulation group and the non-stimulation group with respect to total trajectory length, outer circumference area, rectangle area, or effective value area. Further research is required using different test subjects and research methodology.

Keywords: Shiatsu, plantar region, variance of center of gravity, balance in the upright position

I.Introduction

In shiatsu therapy, the plantar region is approached based on a variety of interpretations depending on the symptoms involved, with numerous accounts of its perceived efficacy based on experience.

However, few studies have been conducted on the effects on the locomotor system of Japanese manual therapies to this region.

In this study, as an initial step in clarifying the effects of shiatsu therapy on the muscles and structure of the plantar region and the consequent effect on locomotor function, we progressed to the pre-experimental stage in the measurement and analysis of changes to standing balance using a stabilograph. This is an interim report on the results obtained and summary of our ongoing research.

Ⅱ.Methods

1.Subjects

Research was conducted on four healthy males (mean age: 30 ± 10.68 years old) who were students at the Japan Shiatsu College. Test procedures were fully explained to each test subject and their consent obtained.

2.Test location and period

Testing was conducted in the lounge space at Japan Shiatsu College between January 29 and February 5, 2015.

3.Measurement procedure

Center of gravity sway was measured using a stabilograph (Gravicorder GS-10 Type C; Anima Corp.). Each measurement was recorded for 1 minute while subjects stood with the medial borders of their feet together, arms crossed over their chests, and eyes closed. Results were obtained for 10 measurement criteria (total trajectory length, unit trajectory length, unit area trajectory length, outer circumference area, rectangle area, effective value area, sway mean center deviation X-axis, sway center deviation X-axis, sway mean center deviation Y-axis, and sway center deviation Y-axis).

4.Stimulation

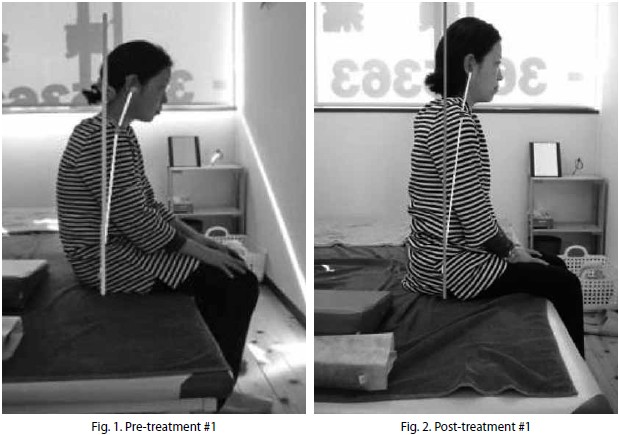

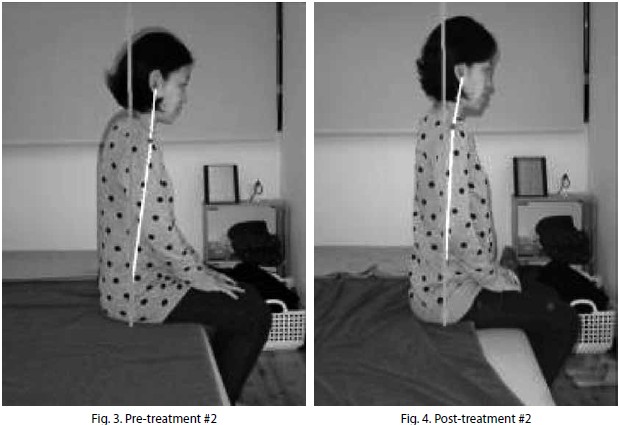

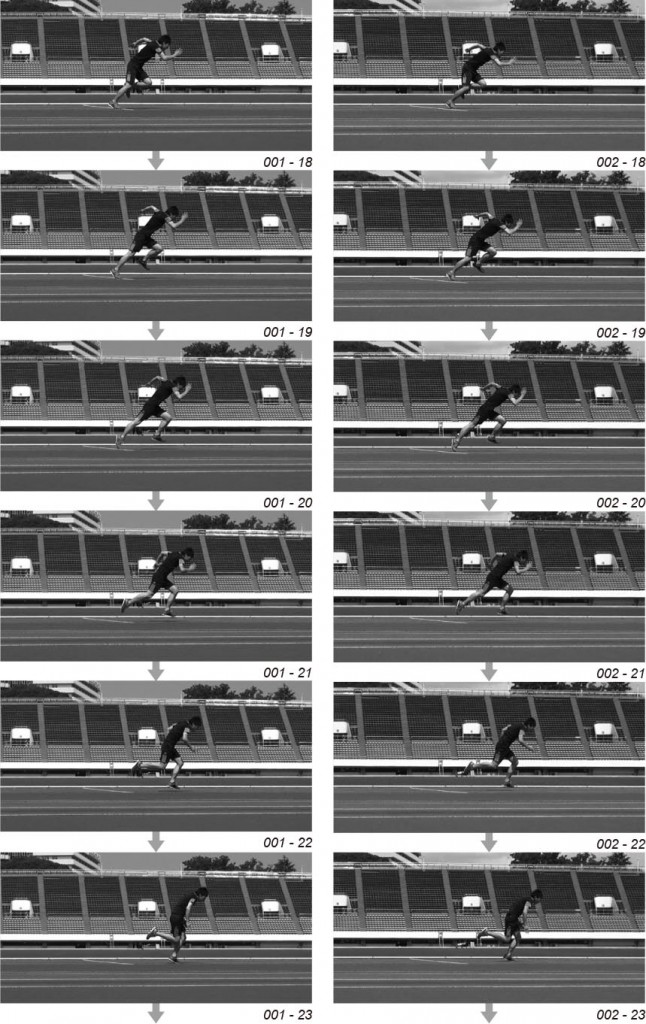

(1)Area stimulated

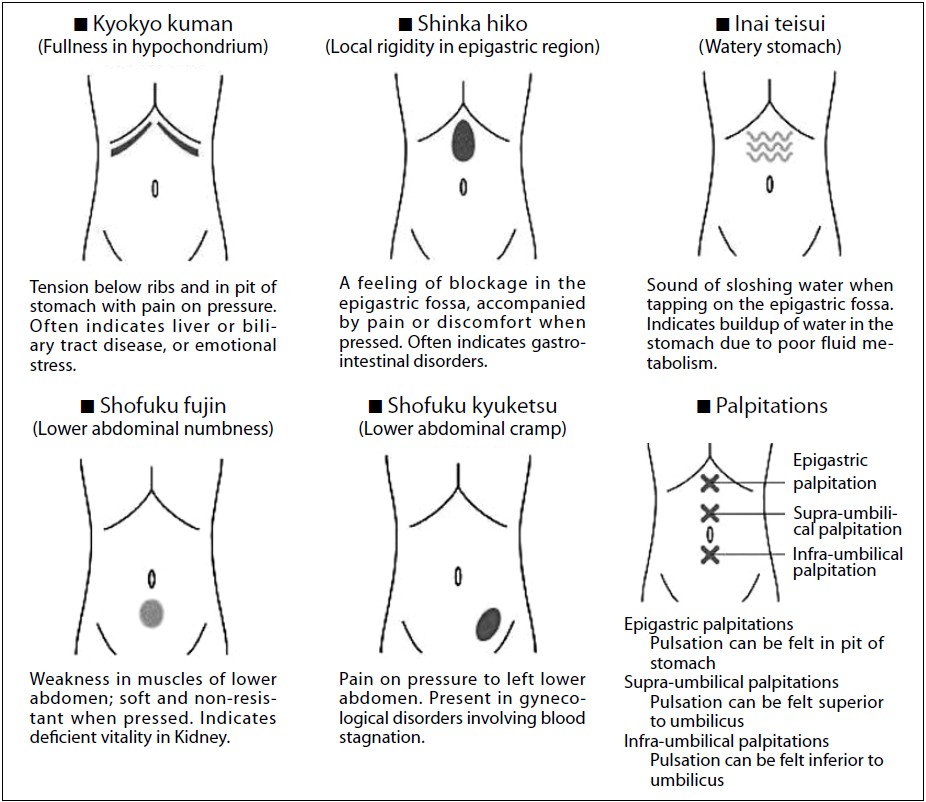

In accordance with the basic treatment points employed in Namikoshi shiatsu, 4 points were stimulated between Point 1, located in the plantar region between the bases of the second and third digits, and the edge of the heel, using 2-thumb pressure with the test subject in the prone position (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. 4 points of plantar region

(2)Duration and method of stimulation

Pressure was applied for 3 seconds to each of the 4 points, repeated 3 times, then single-point pressure was applied to Point 3 for 3 seconds, repeated 3 times, with a total duration of approx. 1 min 42 sec for both feet. Treatment was applied using standard pressure (pressure gradually increased, sustained, and gradually decreased), with pressure regulated so as to be pleasurable for the test subject (standard pressure) 1.

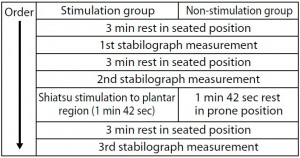

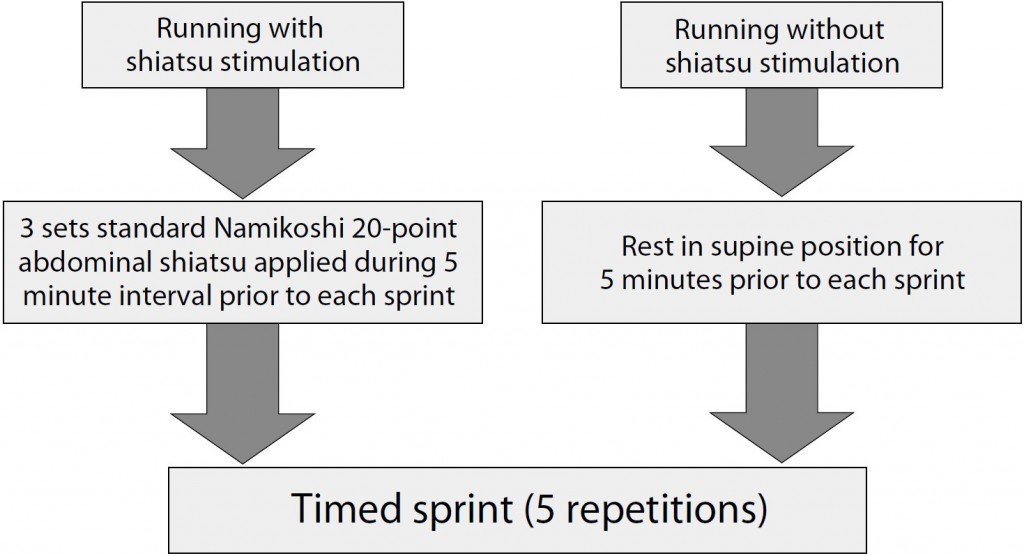

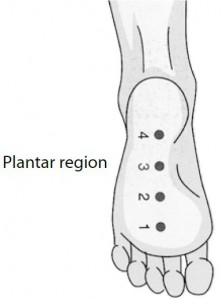

5.Test procedure

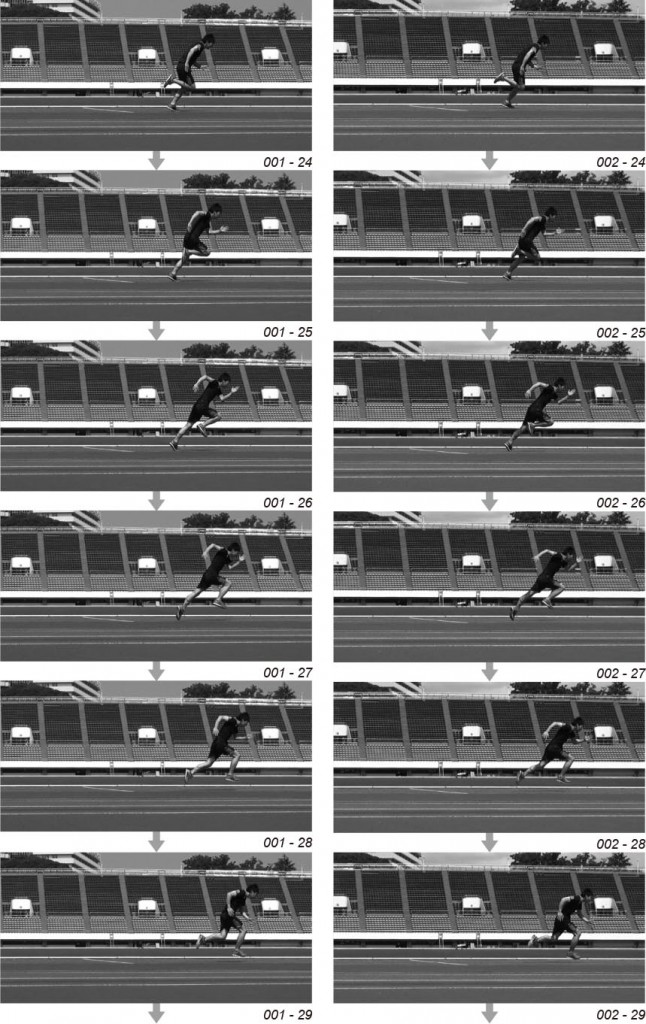

In order to average the test subjects’ learned behavior, they were randomly divided into two groups of two, Group A and Group B. Group A was scheduled to act as the non-stimulation group first, then as the stimulation group, while Group B acted first as the stimulation group, then as the non-stimulation group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Test schedule and learned behavior averaging

(1)Stimulation group

The procedure was performed as follows:

1) 3 min rest in seated position

2) 1st stabilograph measurement

3) 3 min rest in seated position

4) 2nd stabilograph measurement

5) Shiatsu stimulation to plantar region

6) 3 min rest in seated position

7) 3rd stabilograph measurement

(2)Non-stimulation group

The procedure was performed as follows:

1) 3 min rest in seated position

2) 1st stabilograph measurement

3) 3 min rest in seated position

4) 2nd stabilograph measurement

5) 1 min 42 sec rest in prone position

6) 3 min rest in seated position

7) 3rd stabilograph measurement

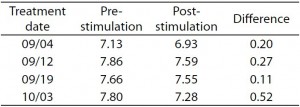

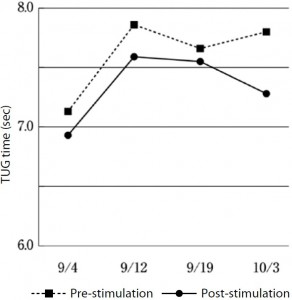

6.Statistical processing

Of the data obtained from the stabilograph, measurements for total trajectory length, outer circumference area, rectangle area, and effective value area were compared between the non-stimulation group and the stimulation group by subjecting data on change rates between the 2nd and 3rd stabilograph measurements to t-testing.

Ⅲ.Results

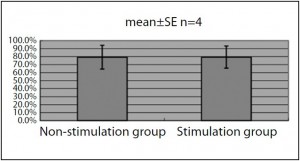

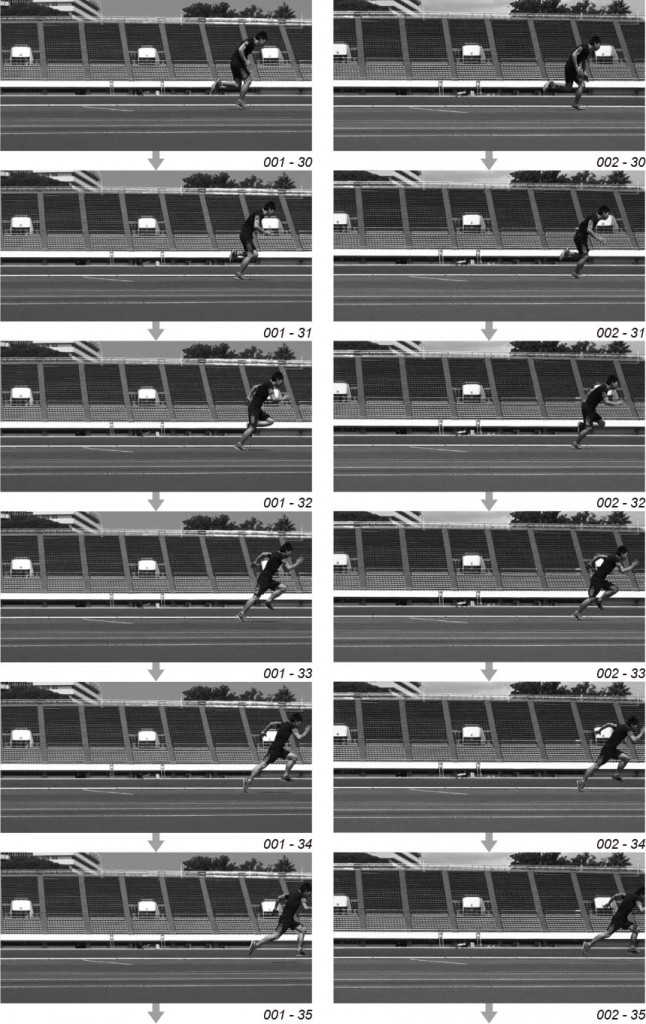

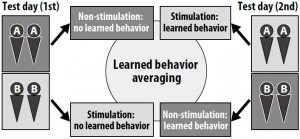

1.Total trajectory length (Fig. 3)

Compared to the non-stimulation group, which had a change rate of 85.5 ± 7.2% (mean ± SE), the stimulation group had a change rate of 92.9 ± 7.0%, which was not statistically significant (p<0.595).

Fig. 3. Total trajectory length

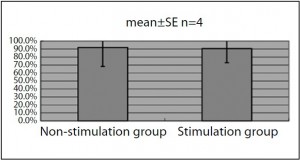

2.Outer circumference area (Fig. 4)

Compared to the non-stimulation group, which had a change rate of 90.6 ± 17.8%, the stimulation group had a change rate of 79.6 ± 13.3%, which was not statistically significant (p<0.744).

Fig. 4. Outer circumference area

3.Rectangle area (Fig. 5)

Compared to the non-stimulation group, which had a change rate of 79.3 ± 14.9%, the stimulation group had a change rate of 79.4 ± 13.9%, which was not statistically significant (p<0.996).

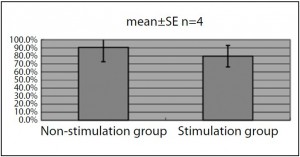

4.Effective value area (Fig. 6)

Compared to the non-stimulation group, which had a change rate of 92.0 ± 23.8%, the stimulation group had a change rate of 90.6 ±17.6%, which was not statistically significant (p<0.975).

Ⅳ.Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of shiatsu stimulation to the plantar region on standing balance. This was based on the hypothesis that shiatsu stimulation would have a similar effect to that reported in existing research showing the effect on standing balance of sensory stimulation to the plantar region 2~6.

In this study, which was still at the preexperimental stage, we were not able to obtain data or statistical results to substantiate the effect on balance of shiatsu to the plantar region. However, each sample observed suggested a trend in the effect of shiatsu stimulation, so there is a chance that a different result will be obtained when testing is conducted with a larger sample size.

On the other hand, all measurement values obtained from this sample were from healthy test subjects considered to be within the standard range 7. It was assumed that, for test subjects within such a range, measurement values would be easily variable based on physical condition, a factor which cannot be averaged out through uniform test procedure. For this reason, it is difficult to fully investigate the effect of shiatsu stimulation on standing balance using the measurement data obtained from a stabilograph alone.

In future study, it will be necessary to consider an experimental method that includes examination of test subjects and the use of other measurement criteria in addition to the stabilograph, with integrated analysis of the results obtained.

Ⅴ.Conclusion

Shiatsu stimulation of the plantar region in four healthy test subjects did not produce a statistically significant change in measurement values using a stabilograph.

Testing of the effect of plantar region shiatsu on standing balance was insufficient due to the limitations of the test procedure employed at this stage, necessitating a reexamination of the methods employed in testing.

VI.References

1. Ishizuka H et al: Shiatsu ryohogaku: 96, International Medical Publishers, Ltd. Tokyo, 2008 (in Japanese)

2. Okubo J et al: Sokuseki atsujuyouki ga jushin doyo ni oyobosu eikyo ni tsuite. Jibirinsho 72: 1553-1562, 1979 (in Japanese)

3. Ito A et al: Sokutei sokuakkaku ga ritsui shisei no jushin doyo ni ataeru eikyo. Nihon rigaku ryoho gakujutsu taikai 2004: A1113-A1113, 2005 (in Japanese)

4. Utsunomiya Y et al: Kankaku shigeki ga seiteki ritsui ni oyobosu eikyo. Nihon rigaku ryoho gakujutsu taikai 2005: A0853-A0853, 2006 (in Japanese)

5. Kamei S et al: Sokutei no kankaku shigeki ga jushin doyo ni ataeru eikyo ni tsuite. Aino gakuin kiyo 20: 27-40, 2006 (in Japanese)

6. Nose T et al: Boshi sokuteibu he no shokuatsu shigeki ga shisei seigyo ni oyobosu eikyo. Nihon rigaku ryoho gakujutsu taikai 2009: A4P2047-A4P2047, 2010 (in Japanese)

7. Imamura K et al: Jushin doyo kensa ni okeru kenjosha data no shukei. Equilibrium research, supplement 12: 15-23, 1997 (in Japanese)