Keisuke Okubo, Maho Nakano

Japan Shiatsu CollegeShiatsu Department

Hiroyuki Ishizuka

Japan Shiatsu CollegeShiatsu instructor

Abstract : Sports are receiving increasing attention in Japan ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. The goal of this study was to verify the effect of standard Namikoshi shiatsu therapy on sports performance.

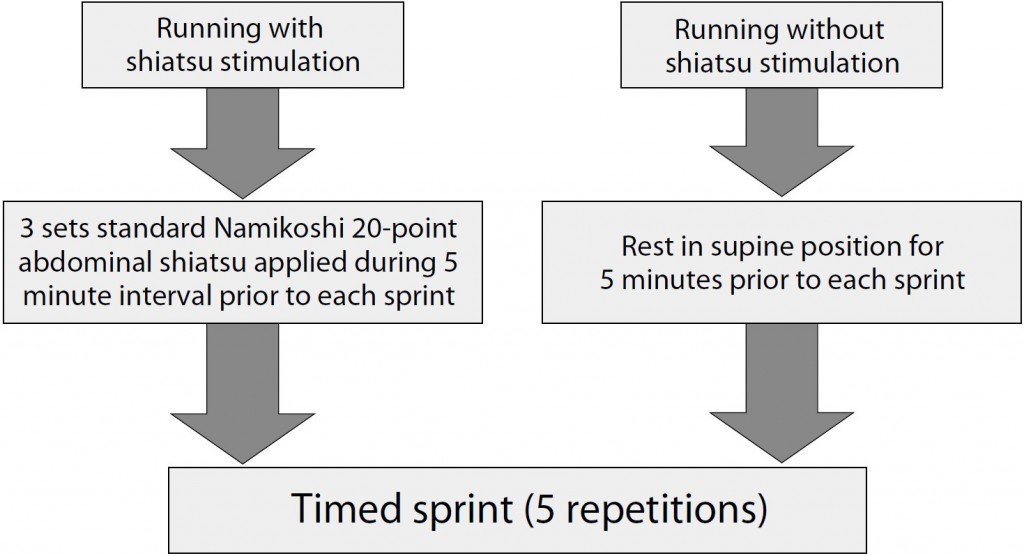

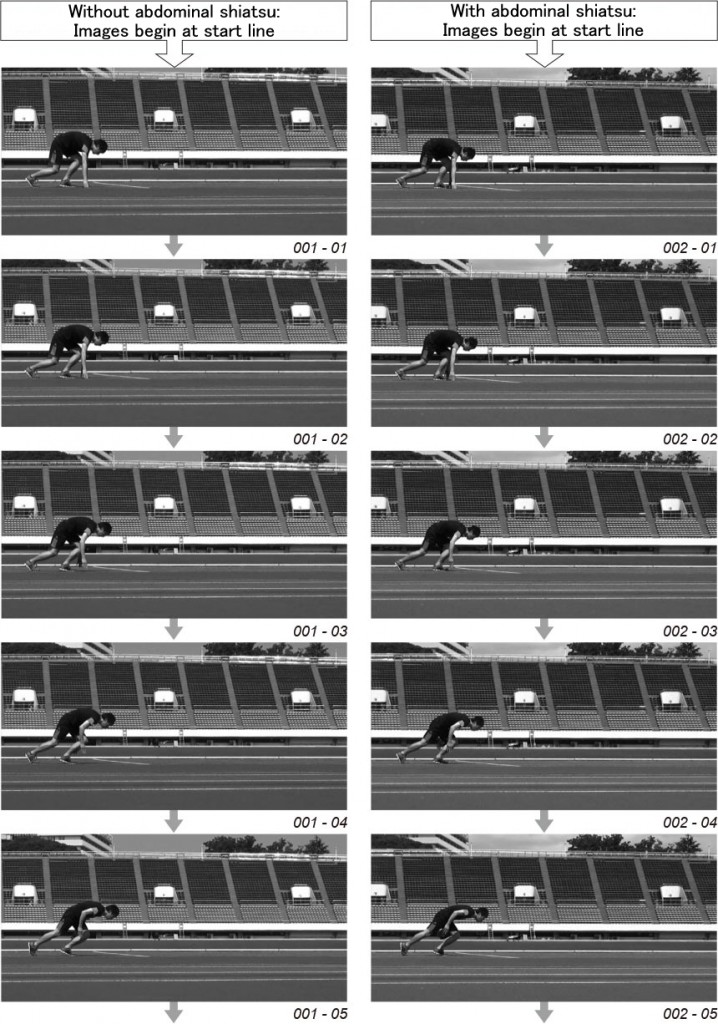

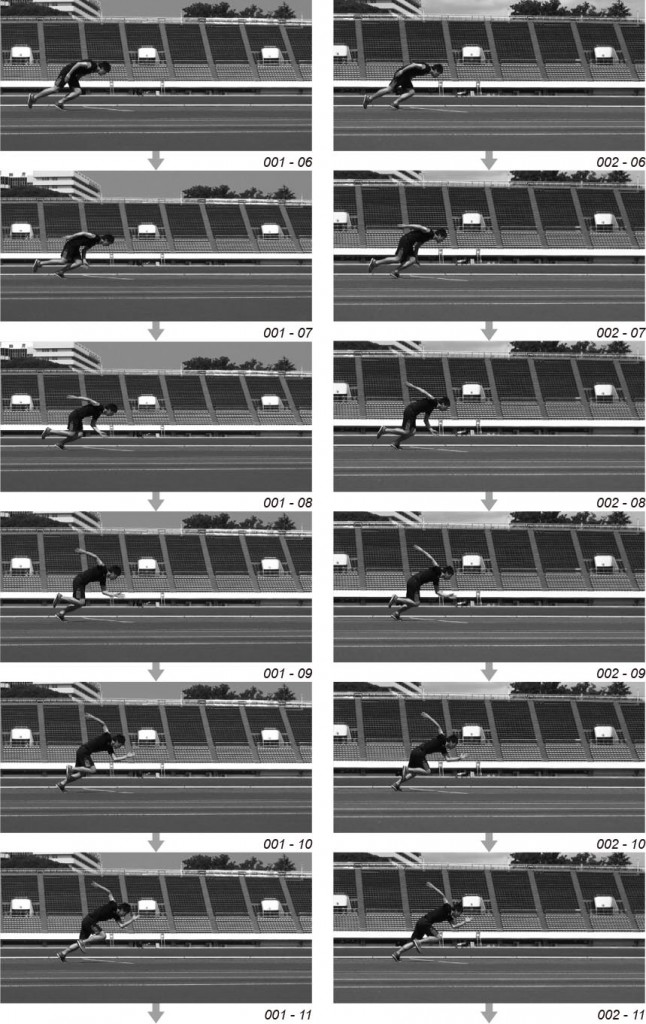

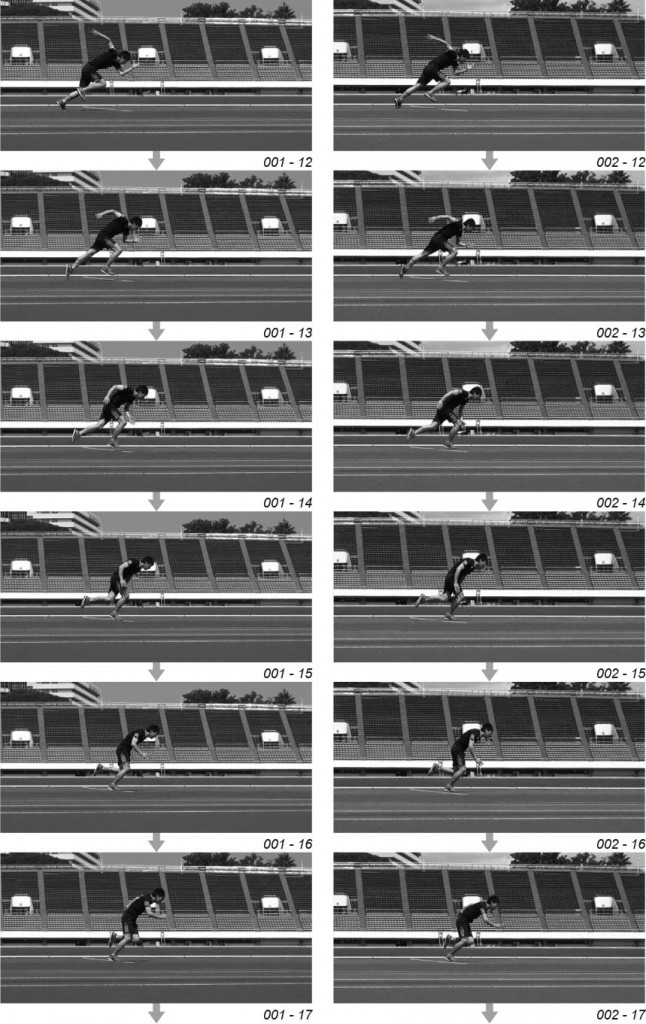

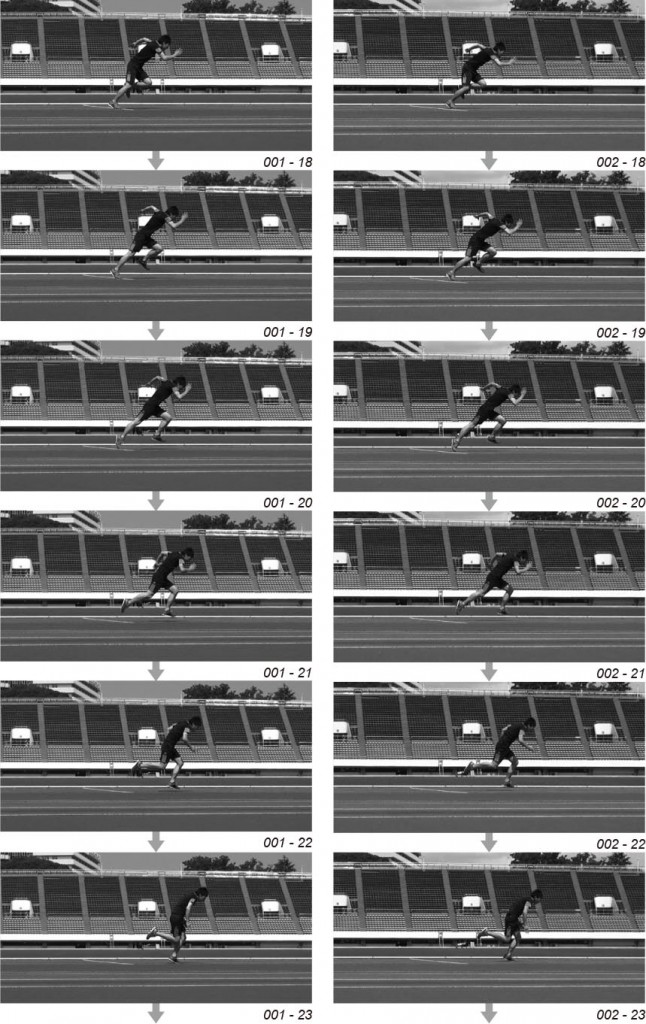

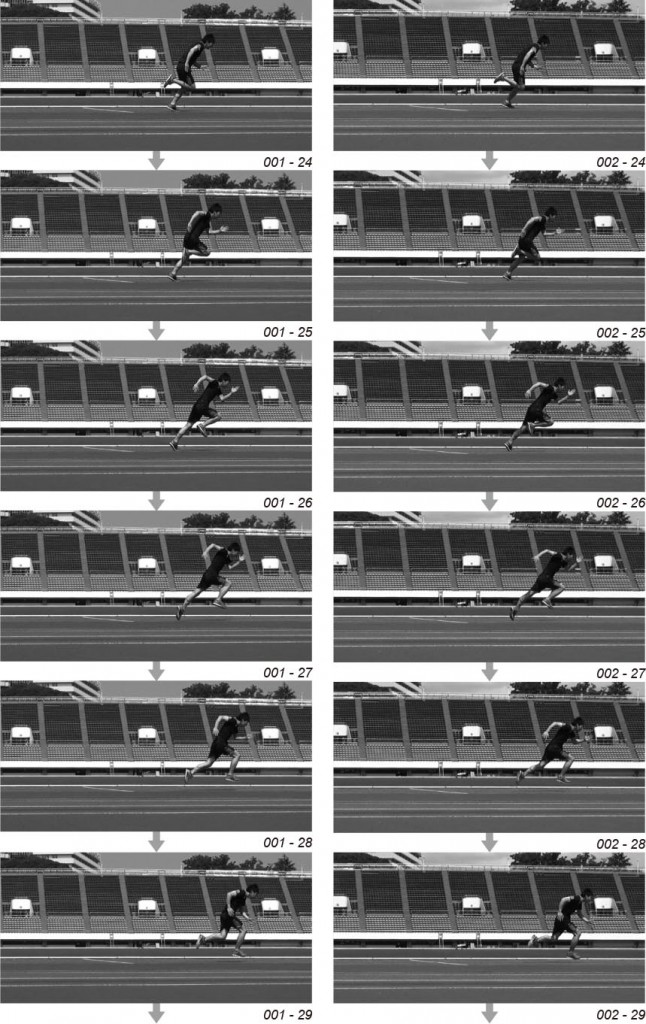

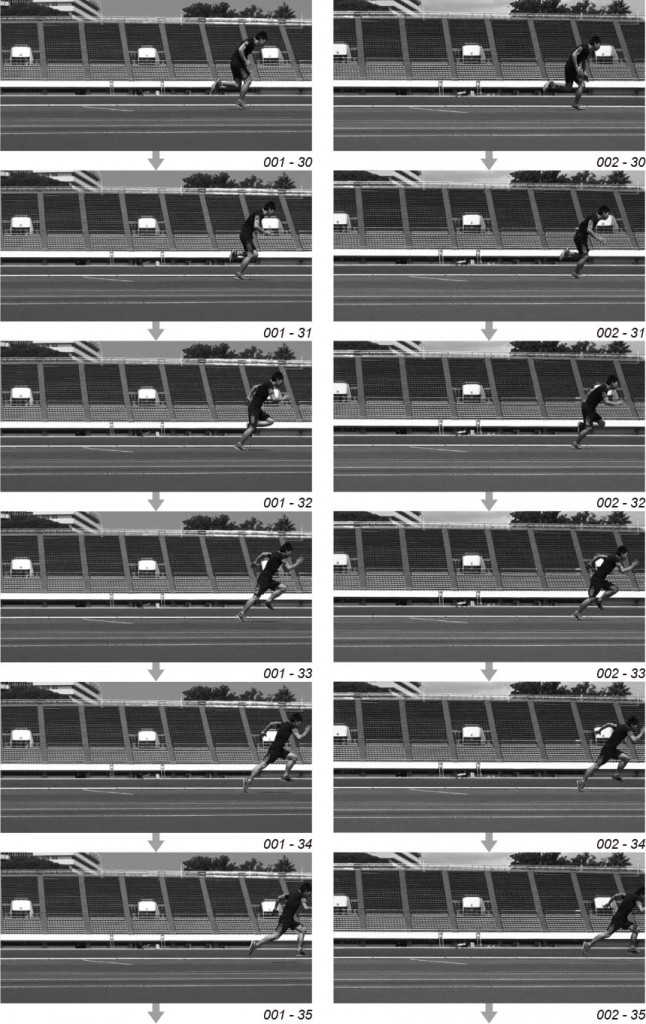

After adequate warm-up, the test subject performed five 50-meter sprints separated by 5-minute rest intervals. The sprints were timed and photographed using a fixed camera to facilitate running posture analysis. Abdominal shiatsu, consisting of the standard 20 points on the abdomen, repeated 3 times, was applied before the initial run and during each 5-minute interval. During control testing, the subject spent the same time resting in supine position. Testing was performed on different days for shiatsu and control sessions.

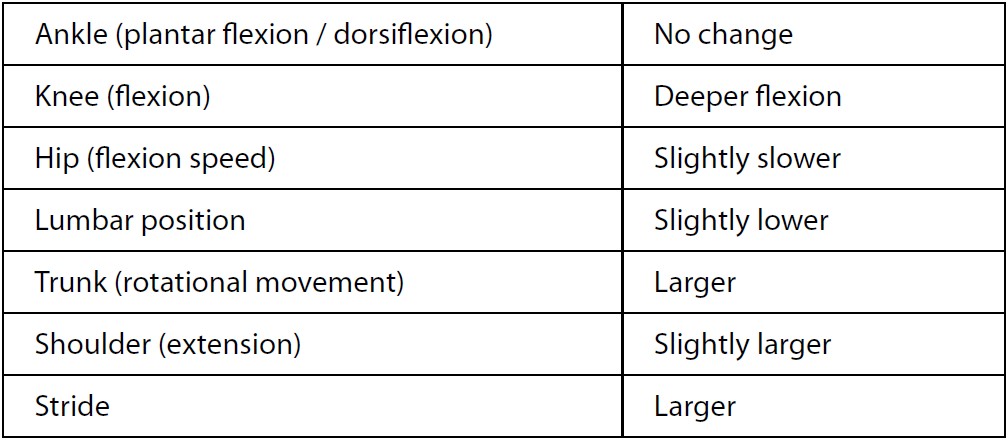

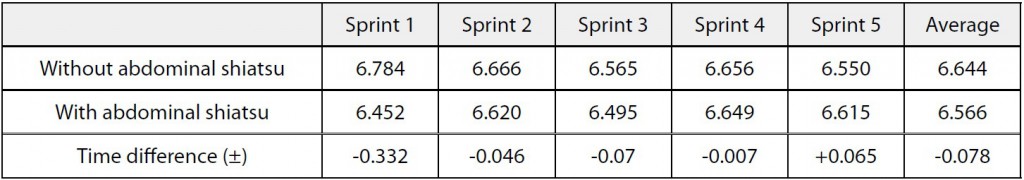

On average, sprint times were shorter when shiatsu had been applied. Comparison of photographic images also showed changes in trunk rotation, knee flexion, and stride length. These results suggest that Namikoshi standard abdominal shiatsu consisting of pressure to 20 points on the abdomen may have positive effects on sprint performance.

Keywords: Shiatsu, run, sprint, abdominal region, abdominal pressure, trunk, exercise, time, 50m, track and field, manipulative therapy, angular motion, image, rectus abdominis, obliquus externus abdominis muscle, obliquus internus abdominis muscle, Olympic, length of stride, twist, motion, ROM, range of joint motion, joint, load, track, race, performance, massage, start, dash, run, crouch start, running motion, abdominal region shiatsu based on Namikoshi shiatsu therapy’s standard procedures

I.Introduction

In this study, we examined the effect of standard Namikoshi 20-point abdominal shiatsu 1 applied to a runner prior to running a 50-meter sprint on ankle, knee, trunk, and shoulder joint ROM, hip flexion speed, and starting hip position, and verified the accompanying changes to stride length and run time.

Measurements were taken after applying shiatsu stimulation to the test subject on August 15, with control measurements taken on August 2 when the test subject had received no shiatsu stimulation. Shiatsu stimulation consisted of standard Namikoshi 20-point abdominal shiatsu, repeated 3 times, before the initial run and during the 5-minute rest interval prior to each of 5 runs. Adequate stretching was carried out prior to running 2.

Ⅱ.Methods

Dates

August 2 and 15, 2015

Location

Komazawa Olympic Park athletic field, straight track

Test subject

27-year-old male Weight: 52 kg Height: 161 cm

Played soccer from elementary school to university

Equipment

CASIO Digital Sports Stop Watch HS-70W

Imaging equipment

SONY HANDYCAM HDR-CX420

iPhone 6plus

Editing application

Adobe premiere pro CC 2015

Adobe photoshop CC 2015

III.Results

Table 1. Comparison of times (sec) with and without abdominal shiatsu

IV.Discussion

The short-distance running cycle can be divided into two phases: (1) the support phase (when the sole of the foot is in contact with the ground); and (2) the recovery phase (when the sole of the foot is not in contact with the ground). Phases (1) and (2) can each be further divided into three sub-phases. The (1) support phase includes (1)-1 foot strike (the period when a portion of the sole of the foot is in contact with the ground); (1)-2 mid support (The period from when the sole of the foot is in full contact with the ground, supporting the body’s weight, to immediately before the heel loses contact with the ground); and (1)-3 takeoff (the period from when the heel loses contact with the ground to when the toes leave the ground). The (2) recovery phase includes (2)-1 follow-through (the period from when the sole of the foot leaves the ground to when rearward motion of the lower leg ends); (2)-2 forward swing (the period when the lower leg is moving from back to front); and (2)-3 foot descent (the period immediately prior to when the sole of the foot makes contact with the ground). Specific muscles are active during each of these phases, which may vary depending on running speed. When observing the muscles active while running, the abdominal muscles are strongly active only when running 100 m at an average speed of 36 km/h, as compared to 1 km at an average speed of 12 km/h or 16 km/h. During the running cycle, strong abdominal muscle activity is observed from (1)-2 to (2)-2 3.

The reason abdominal muscle activity is only observed in short-distance running is due to the strong angular momentum generated between arm swinging and the pelvis. While running, the pelvis produces rotational motion on a vertical axis, generating angular momentum around the vertical axis. Arm swinging is important for reducing trunk deflection due to this motion; in practice, the angular momentum produced by arm swinging eliminates the trunk deflection due to pelvic angular momentum. This is a distinguishing characteristic of short-distance running 4.

In running there is an ideal leg trajectory. According to research conducted using a sprint training machine, leg motion effectively utilizes flexible twisting and rotational motions in the pelvis and trunk and is also necessary to adroitly maintain balance. Also important is that this motion originates in the epigastric fossa, around the level of the upper lumbar and lower thoracic vertebrae 5.

Muscles thought to be affected by abdominal region shiatsu include the muscles related to maintaining abdominal pressure (diaphragm, rectus abdominis, external abdominal obliques, internal abdominal obliques). When these abdominal wall muscles contract in coordination with the pelvic floor muscles, intra-abdominal pressure rises. It is known that increased intraabdominal pressure significantly reduces the load placed on upper and lower lumbar intervertebral discs 6.

Based on the above discussion, one possible explanation for improved running performance and shorter times recorded in this study is that abdominal shiatsu resulted in more coordinated performance of muscles involved in maintaining intraabdominal pressure and improved trunk stability. It is also possible that improved response time from the start of the sprint to the first step resulted in faster running times, but analysis would be problematic at this stage.

Ⅴ.Conclusions

Abdominal shiatsu does not directly affect the lower limbs, which are the focus of running. However, it may have an effect on the trunk, from where such motion originates, contributing to more ideal motion in the upper and lower limbs.

Nevertheless, many points in this study remain unclear, and it is possible that there would be no effect on middle or long distance running times, where abdominal muscle activity is less apparent. More specialized testing and analysis is required.

References

1 Ishizuka H: Shiatsu ryohogaku, first revised edition, International Medical Publishers, Ltd. Tokyo, 2008 (in Japanese)

2 Sugiura S: Sutoretchingu & womuappu buibetsu tekunikku to kyogibetsu purogruramu. Oizumi shoten, 2008 (in Japanese)

3 Kawano I, Tsukuba Daigaku et al editorial supervision: Konin asuretikku torena senmon kamoku teksuto, dai 6 suri. Bunkodo, 2011 (in Japanese)

4 Shikakura J et al editors, Kawano I et al editorial supervision: Konin asuretikku torena senmon kamoku tekisuto, dai 7 kan asuretikku rehabiriteshon. Bunkodo, 2011 (in Japanese)

5 Kobayashi K: Ranningu pafomansu wo takameru supotsu dosa no sozo. Kyorin shoin: 42, 2001 (in Japanese)

6 Sakai T et al translator: Purometeus kaibogaku atorasu kaibogaku soron undokikei dai 2 ban. Igaku shoin, 2013 (in Japanese)

Additional reference

Saito H: Undogaku. Ishiyaku Shuppan, 2003

Filming cooperation: Clothing Valley Digital Studio